Law has mandated green crackers this Diwali, but there’s likely to be a rainbow on the quick commerce landscape.

Shoppers beat the inflation woes during Diwali last year and splurged a record INR 1.25 Lakh Cr. With retail inflation pegged at a chilling 2.6% and economy zipping at 6.8% this fiscal, you can’t blame the quintessential Indian buyer for being a little more extravagant this time.

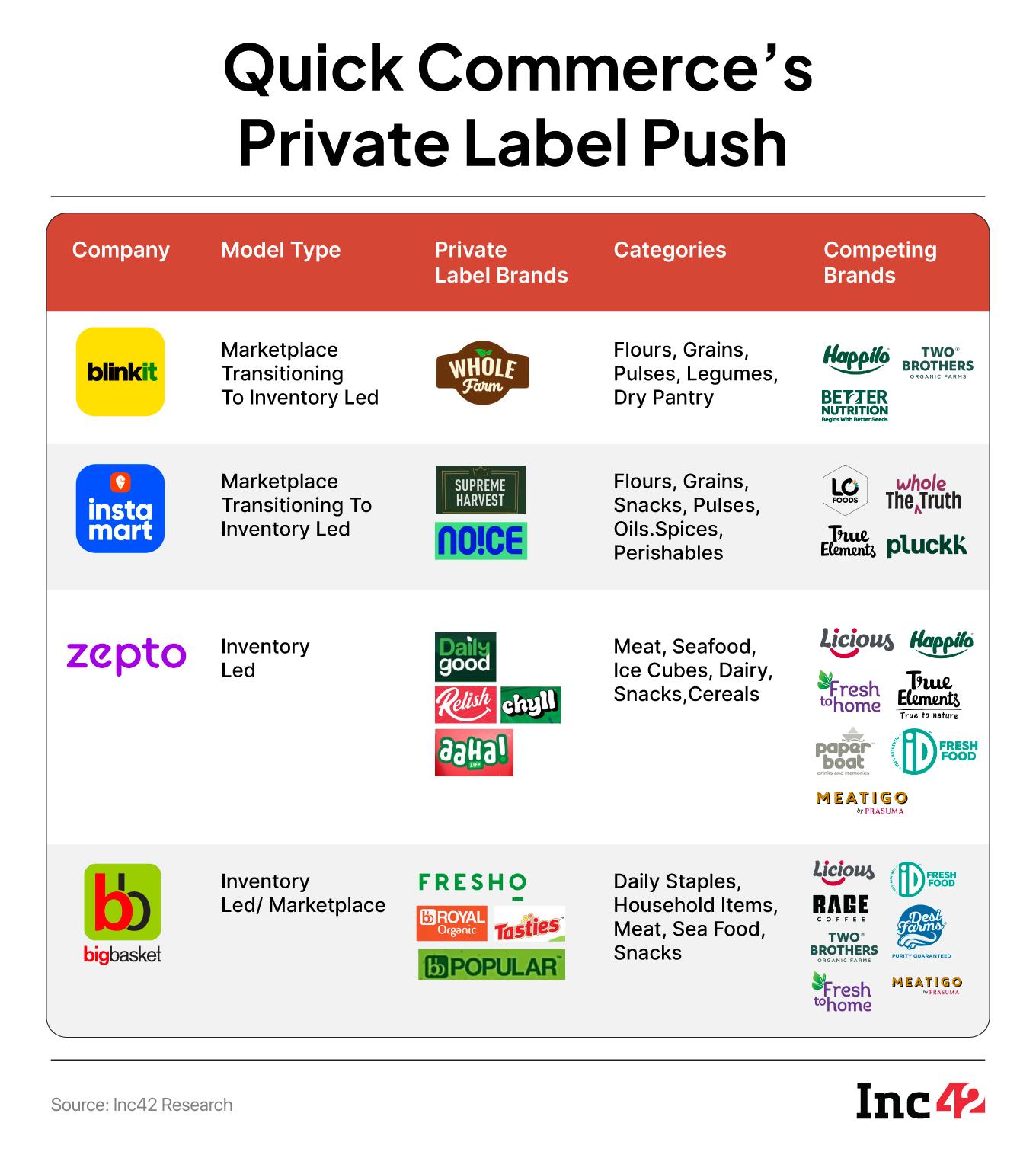

The festive season is in full swing and the buying binge is in full throttle. With quick commerce reshaping the way people shop, there’s a frenetic rush among platforms to launch private labels and cash in on the frenzy.

In fact, in the last four years, private labels clicked more resoundingly than perhaps imagined in markets that fostered countless luxury marques. Nearly 75% US and 85% European consumers have switched to platform-owned brands or private labels.

In India, the raging popularity of private labels is more pronounced during these festive days. Although there’s no specific data available on their share in the retail pie, they make up a substantial chunk of total sales, given that over 52% Indian shoppers are more inclined to private labels than traditional brands.

Quick commerce platforms paved the way for a niche category of D2C brands, but now those very same brands may have to contend with platform-owned private labels.

After crossing $5 Bn in gross merchandise value (GMV) in FY25 and reporting more than $1 Bn in revenue combined, the quick commerce Big Three – Blinkit, Instamart and Zepto – proved that they have aced the volume game, though their struggle on margins continued.

In sync with a sustained rise in online buying, Blinkit has transitioned from a marketplace model to an inventory-led model, while Instamart has scaled its private label business to control pricing, assortment, listing on apps and eventually make profits.

The inventory-led model, enabled by its Indian-Owned and Controlled Company (IOCC) status and effective from September 1, allows Blinkit direct sourcing and stocking of private labels like Whole Farm. It boosts both margins and control.

Instamart, on the other hand, had a significant presence in the daily staples category through its private label Super Harvest that was launched in 2022 and Noice, a beverage snacks brand rolled out earlier this year.

Zepto has been vocal about growing business in its meat and sea foods brand Relish and daily staples brand Daily Good that contribute a major chunk to its topline.

Tatas-backed Big Basket, despite reporting a decline in FY25 revenues, has an INR 4,000 Cr private label business that offsets some of the business challenges the company faced in quick commerce.

While the platforms may have adopted different strategies and forayed into distinct categories, the intention remained the same: improve the margin levers and gain more control over pricing. But, as the quick commerce players make their intent clear towards an aggressive push for inventory control and pricing, it begins to pinch D2C brands. By owning inventory and curating private labels, these platforms are no longer mere distributors, they are competitors now.

And, D2C Brands Face The HeatOne of the clearest structural levers quick commerce platforms now wield is margin arbitrage. “When a platform sells its own private label, it can capture higher margins in some of the high-intent purchase categories, compared to the commission or fee it earns from a third-party D2C brand. This delta in economics gives the platforms a strong incentive to promote in-house SKUs aggressively,” Satish Meena of Datum Intelligence told Inc42.

The platforms can use this margin advantage to engage in ‘halo subsidies’ or temporarily pricing private label SKUs more aggressively, bundling them with loyalty programmes, or cross-selling them to lock-in customers.

“The platforms also control the algorithmic feeds, search rankings, and recommended or trending slots. A platform-sponsored SKU or, private label, can be prioritised higher in listings, This tilts discoverability in favour of in-house brands, making it harder for independent D2C labels to maintain visibility unless they spend on advertising, which again adds to the platform’s revenue,” Meena said.

Because they control both pricing and logistics, the platforms can absorb short-term losses to push private labels. They can also build loyalty schemes like membership, cashback and preferential treatment that further tilt consumer choice towards in-house brands.

Unlike large FMCG brands that have a loyalty factor associated with them and pay lower commissions to quick commerce platforms, D2C brands may find their growth slowing with reduced conversion rates. They now need to diversify their distribution through offline channels, alternative platforms, or owned channels.

Karan Taurani of Elara Capital, though, doesn’t see any significant threat to D2Cs, stating that these consumer tech companies have raised sufficient capital and have derisked their businesses to an extent that the private label push of quick commerce platforms won’t impact them majorly.

For D2C players accustomed to storytelling, brand narratives, and premium positioning, the pressure will now increase on supply chain, consistency, pricing, and agility. “It means that brands will have to innovate to deliver superior products which the customer in quick commerce platforms is eyeing,” Daily staples brand Better Nutrition founder Vivek Rastogi said.

A Tilted Playing Field For Private LabelsOn the face of it, the push to private label products seems to be a deft move by quick commerce platforms, especially when uncertainty in the economic and geopolitical landscape has kept global markets in a state of heightened volatility for the last few years.

A look at the global trend shows that at least 47% of shoppers are opting to buy less and around 44% of shoppers across generations have begun shifting to discount stores. One in every four shoppers are switching from branded stores to generic retailers. All these indicate a strong emphasis on affordability, which is a major factor behind the rise in private labels.

On the home front, organised retail throws up an analogy. Supermarkets like DMart, Reliance Retail and Big Bazaar have long pushed their private labels. Yet, FMCG and branded products continue to rule their shelf space.

Brands with strong equity, marketing, and consistent distribution managed to coexist. Private labels could not fully displace the legacy brands, but they did raise the bar for efficiency, differentiation, and supply chain rigor.

Taurani of Elara Capital gave the instance of Nykaa. The beauty marketplace has launched a major chunk of private labels, but they have only managed 14-18% of the overall sales on the platform.

“Marketplaces imitating their success in private labels is not a given,” cautioned Meena. He said that even in the US, where Amazon has private labels, they contribute only about 10% of total revenue in many catalogue verticals.

Categories In The Eye Of A StormNot all product categories are equally at risk from private labels. The most vulnerable have common traits like high purchase frequency, low differentiation, and simpler supply chains. Products like flours, pulses, rice, snacks, packaged foods, edible oils are prime targets for private label experimentation. Some of these high-intent products like milk, bread and egg deliveries are more nuanced with demand in specific hours of the day.

Swiggy Instamart’s Supreme Harvest has grown staples presence across multiple products, Zepto’s Daily Good and Blinkit’s Whole Farm are also present in these micro-categories. For Big Basket, BB Royal and BB Daily are driving huge GMV.

Analysts noted that the daily staple products deliver an average margin of 7-8% which helps the platforms improve their profitability. Industry experts believe that even if the in-house products can crack 8-10% of overall sales, this would significantly boost their margins.

Personal care and household items like soaps, detergents, cleaning supplies, sanitisers, and various chemicals are repeat-buys, low-involvement products with modest differentiation.

Ready-to-drink beverages, bread, packaged juices, etc. are also under threat. While cold-chain logistics increase complexity, the high turnover and impulse nature make them attractive for private label play.

While many of these categories continue to be dominated by FMCG giants like ITC, HUL and Nestle, many new-age D2C brands present in such categories have raised capital over the last few years that include Super Harvest, Two Brothers, Better Nutrition, Soulfull, Lo Foods, Zoff Foods, Sugar Watchers, The Health Factory, Protein Chef among others.

The Qcom Blueprint And D2C BluesBlinkit is on an aggressive scaling spree. In Q1 of FY26, Blinkit’s revenue surged 154% to INR 2,400 Cr over the last year, with 243 new dark stores and micro-fulfillment outlets taking the total count to 1,544.

Analysts expect Blinkit’s shift to inventory model will help margins. One estimate suggests a 1% margin expansion (as percent of net order value) over the next two to three quarters. Kotak Institutional Equities notes that it will bring Blinkit’s accounting and operating behaviour closer to a retail model, but at the cost of increased risk on inventory, wastage, and logistics.

The aim is not just growth but eventual EBITDA breakeven. Another estimate projects EBITDA break-even by March 2026. Blinkit, however, continues to battle with losses. Its Q1 FY26 adjusted operating loss stood at INR 162 Cr, while margins remained negative. But, the company bets that scale and visibility will close this gap.

Rival Instamart, on the other hand, is pushing its private label brand Noice and Supreme Harvest as core margin levers. In recent months, Noice has expanded to over 200 SKUs across 13 categories, collaborating with 40 local kitchens and manufacturers. The push into perishables is also underway.

IPO-bound Zepto has a sizable presence in daily staples and meat categories that contribute significantly to the platform’s annual revenue run. It is also run on a full-fledged inventory model where the platform purchases the stocks from wholesalers and has full control on pricing and assortment.

The blueprints of the Big Three are based on the boom in India’s $5.38 Bn quick commerce market that’s likely to reach $11.08 Bn by 2030 at an annual growth rate of 15.54%. In Q1 of FY26, the sector grew less than 20%, but Blinkit and Instamart outpaced with 25% and 22% GOV growth.

As the platforms look beyond metros and Tier I cities, private labels become all the more relevant for their pricing and availability quotients.

It is unlikely that the dazzle of quick commerce private labels will darken the fate of D2C brands overnight. Instead, what is more likely is a shakeout. Weaker brands may struggle or exit, while those that raise the bar will survive and even thrive.

[Edited By Kumar Chatterjee]

The post Private Label Diwali For Quick Commerce Giants appeared first on Inc42 Media.

You may also like

Women's WC: Will take it on myself as collapse started from me, says Smriti takes blame for India's loss

Kiran Rao reveals Ravi Kishan's rule, which he broke for her in 'Laapataa Ladies'

The UK seaside town with high street in crisis - 40 stores closed on two streets alone

May light of truth, justice always illuminate our path: Mallikarjun Kharge's Diwali greetings

Rachel Reeves warned UK 'woeful' on key economic issue - 'it could get worse'